I am not sure when it did all start. I know that it is one of those things that my mother somehow passed me along, even though I did not, at the time, want it or understand it, and even though she didn’t suspect that, along the way or because of some transformational process involved in the transference, it would become this particular practice I carry into my heart and my body now.

I know that I’ve seen her struggle with 3 or 4 abortions and 5 childbirths, and I remember her coming back from the hospital every time a little bit more defeated, a little bit more bitter and a little bit crazier.

She would often talk into the mirror at her own reflection or out the windows at the particles of dust and even to us children, for lack of better listeners. Sometimes she talked about not having wanted us kids, not so many of us at least. She would often tell us how all those pregnancies, the long months of nursing and the hard job of taking care of us had destroyed her, slowly but surely. She said she lost her beauty and her health. Her hair tinned, her teeth and bones weakened, her body deformed. She told us stories of loosing her language and speaking a sort of baby tongue after years of being so isolated that we had become her only interlocutors.

The most striking consequence of her apparent inability to exercise any control on her sexuality and her desire or un-desire for maternity was that all the rest of her life had become compulsively micromanaged. Her diet was extremely rigid. She spent innumerable amount of hours scrubbing floors, dusting furniture and washing clothes, in a constant struggle to keep a tight grip on her environment and to hide from the fact that the most important thing she indeed wanted to control had completely escaped her.

My mother was a math teacher. She was, and still is, brilliant and beautiful. She had liked, as a girl, to write poetry and even published some of it. She liked to sing and dance and she had been sort of famous for being the first one in town showing off a 70s style miniskirt.

Of course I’ve never met that girl, since by the time I entered her life her menial occupations had taken up all the attention and did not leave her any to read or write, sing or dance.

I remember nonetheless being fascinated as a child by all the things she knew and all the different skills she had (best of all that of storytelling).

She is a great cook, of the best kind, because she knows what food does to our body, which foods is best to eat and when and how to cook them in order to enhance their properties.

She knows everything about herbs and collects them, steeps them, stores them in alcohol solutions in the fridge, takes them orally in form of little pills first time in the morning, and grows them on our second floor balconies .

I still remember her giving me a concoction of ground almonds and honey to cure me from my constant anemia or administering us spoon-fulls of pollen to help us with seasonal change.

When I called her during my freshman year in college in the midst of a full blown depression, she advised me to take Saint John’s Worth at a time when nobody even knew what it was, and so saved me the pain of having to take prescribed medication.

When she developed breast cancer, she started studying unrelentingly about it and she eventually healed herself by changing her diet and taking herbal supplements. She never had to undergo chemotherapy and she was cured of it once and for all.

She told us that she had learned from her father who had been a medical officer in Africa during the second world war and who, though never a doctor, had always been a healer.

Paradoxically, her unique ability to take care of her own body and her refusal to delegate it to a clique of mostly male professionals miserably crumbled when the man who confronted her about it was my father.

Of course at the time I had no idea what a taboo it was, and somehow still is, for any woman to be in the kind of intimate relationship with her own body that is necessary in order to take charge of her own sexuality.

As a child I did not understand why she was so mad at my father, that all powerful, adventurous, unpredictable and fun creature who was, and still is, the object of my absolute love and admiration, as well as the source of some of my worst fears.

Later on, when other men came into my life as a more urgent and manageable target for love and desire, the question of their constant, menacing, indefatigable fertility, wrapped itself around my head in the form of an almost comical desperation. I felt that a sort of biological conspiration was unfolding in my personal life and, as the intellectual and political activist I already was or wanted to be, I was outraged at the amount of time and energy that I was expected to permanently spend in the attempt to protect myself from these most charming and most subtle invaders. I could not, in all honesty, understand why the blame and shame of unwanted pregnancies or abortions always fell upon women, when our bodies are, in comparison to theirs, so delightfully unfertile. Compared to the seemingly endless strive to procreate of a male body, ours appear to have evolved almost entirely for the sake of aimless, unconcerned enjoyment.

So, even though I am naturally and culturally very suspicious of health care institutions, and even though, being brought up as a free spirit in a house full of women, I never considered my gender to be a medical condition (to be kept under close check, to be examined routinely, or to be treated with long term drugs), at the age of 19, when in a state of obtuse enchantment, I decided to try and take the pill.

It did seem like the easiest and most reasonable solution to me at the time and it also apparently pointed me in a direction that was diametrically opposite from the one my mother had taken. It also felt like a grown up and serious thing to do. Something like I was taking sort of a social responsibility towards myself by making my inner environment a poisoned field and giving my lover peace of mind.

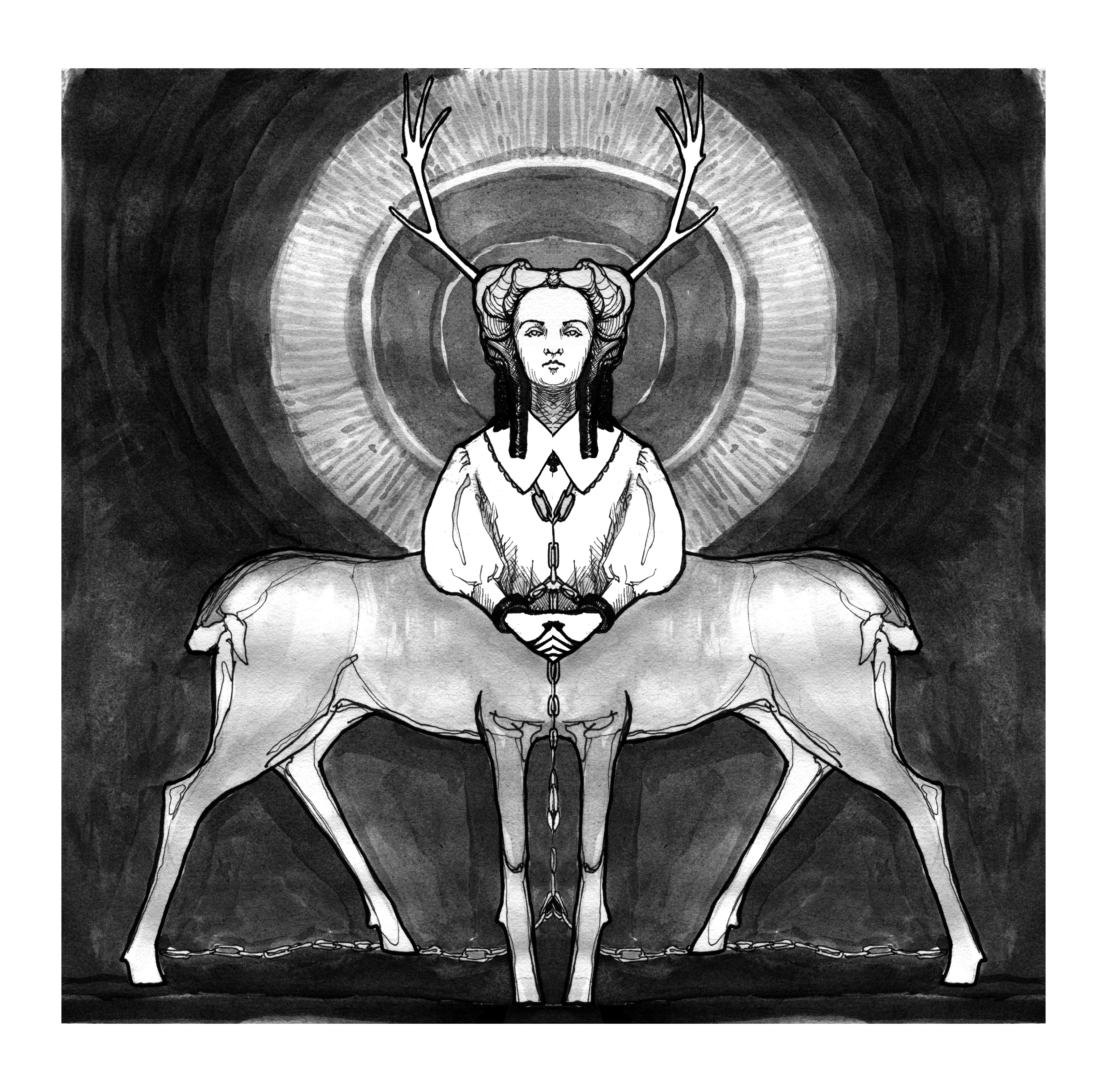

It did not last more than a few months though, because I could not bear the burden of headaches, fatigue and all the other side effects. Also, since I knew very well that my fertility window lasted only two days a month, putting that malignant, alien thing into my body every morning seemed to be like the most vicious of jokes. I felt a sense of weird disembodiment and estrangement. That thing had entirely stopped my periods and replaced them with a sort of fake, light monthly bleeding. It made me feel almost like I had bleached away the wilderness and dangerousness from myself and had become a tame, sterile, emptied-out doll. I understood, in a sort of blurred way, that I had found myself in a place very similar to where my mother had been. Far away from my body, trying to avoid seeing it and erasing all that was ‘inconvenient’ about it.

Since that day I started a journey of discovery and self-discovery and, even though I encountered the term gyno-anarchy only recently, what I have wanted has been to take full control of my sexuality, my fertility and my desire or my refusal to procreate.

I had to learn how to tune in with my body, with its so mysterious and marvelous cycles, with its temperature changes, hormonal picks, micro-contractions and viscous substances. I had to take into consideration season change, stress factors and, because I lived almost all my adult life in collective houses, even that most magical phenomenon known as menstrual synchrony.

I had to learn when to say yes and when to say no. Most importantly, I had to learn how to follow my Principle of Pleasure1.

The first time I read about the Principles of Pleasure, as it was elaborated by Italian feminist thinkers like Carla Lonzi, I didn’t really understand it. Or maybe I did, but it sounded too costly, too difficult and very dangerous to apply to my own life.

The fact is that pleasure really, and not only sexual pleasure, is far from frivolous. It is the very fabric of which our life is made. It is the internal compass that can and should guide us towards a free and authentic life.

The Principle of Pleasure makes us daring and generous. If I follow my pleasure, it will be difficult for me to fall into oppressive traps, abusive relationships and conformist cages because my body is braver than I am and often even smarter. Never my pleasure seeking body will choose security over adventure, stereotypes over curiosity, taboos over discoveries.

One of the strongest images I recall of my first year in the States is that of two young Mormons, kneeling under the rain and praying in front of an abortion clinic.

I did not understand it. I also did not understand why all that revolves around abortion is labeled here with such generic and vague terms, suggesting just the opposite of it, like planned parenthood, reproductive rights or women health.

Coming from a culture where miscarriage and abortion are described with the same word and seen as almost the same thing, I had a lot of problems accepting that it is so difficult for women in this country to say aloud ‘I don’t want to be a mother’ or ‘I don’t want this baby’…to own their desire to be other than procreators.

When recently the funds to planned parenthood were dramatically cut, I realized how much of our lives revolves around institutions, depends on politicians and is delegated to the expertize of a large group of mostly white males. I started thinking of a diversion tactic that I call ‘the strategy of the fool’.

I first encountered something like this when Mario Tronti, my Political Philosophy professor in Siena, gave me to read a little book called Discourse on voluntary servitude, while I was writing my final dissertation. It was written by Etienne De La Boetie around 1550 and it’s based on the idea that to liberate ourselves from tyranny, all we have to do is give it our back and turn a deaf ear to its postulates.

Turn your back and the monster will disappear, turn your back and create a new order , founded upon pleasure, relationships and shared practices, rather that bureaucracies and profit. Internalize the strategy of refusal, apply it to your own body. Refuse to let the approval of majorities and politicians matter all that much and, most of all, do not ever delegate to them the care of what is important to you.

Of course it requires practice, sabotage and diversion and of course it’s not at all that simple, but it does at least turn us into different kinds of heroes, unlikely warriors, brilliant farcical characters like Odysseus in the Iliad, the hero who refused to be a champion and played the fool to avoid a war he did not really care about. Or like Rachel in the Bible, who stole the family idols from the paternal hearth and hid them under her saddle so that, when her father tried to search her, she could turn the contaminations norms against him and say that she was menstruating and so could not be touched.

It allows us to use words like fighting, struggle and warriors, without the fear of falling into the usual male war rhetoric and describing a set of practices that, though not necessarily nonviolent (ending a life process is always a radically violent act), it is not aggressive.

And so I put together a workshop at the Wooden Shoe2, one in which I suggested that we all steal the family idols and play the fool, that we learn about our bodies and what makes them feel happy and loved, that we learn how to best take care of ourselves and of each other, instead of relying on the medical institution.

I met a lot of women there, some of them very young. Some of them, I discovered, didn’t even realize when they were fertile or that it could be tracked down at all, for that matter. Together with them I mostly laughed, a healthy laugh that opened the Pandora’s box of giggles on homemade spermicide and post-fertility hangovers, unveiling the deeply comical side of sexuality.

Some of them are already my new heroes, like Cassie, who soon after started a fertility class for the West Philadelphia Free Skool; like Nicole, who volunteers as a hand-holder at Planned Parenthood, whispering in the ear of frightened women who need to feel loved and accepted; or like Sarah and Toni, who were not even there really, because they are biking down the West Coast on a budget of 4$ a day, to talk to women about menstrual cups and body awareness and who started the Handsome Young Men Project , where men are encouraged to stop telling women what to do with their bodies and start instead a dialogue that includes learning and sharing new, woman -loving practices.

Oh… and BTW, they just made it to LA.